By Clint Alley

“You don’t have to sugarcoat it. My great-granddaddy was a carpetbagger.”

The voice on the other end of the phone burst into a jovial peal of laughter, easing my discomfort and making me laugh, too. I was in the middle of a big research project, and calling someone’s ancestor a carpetbagger still carried repercussions in Tennessee, even in the 21st century.

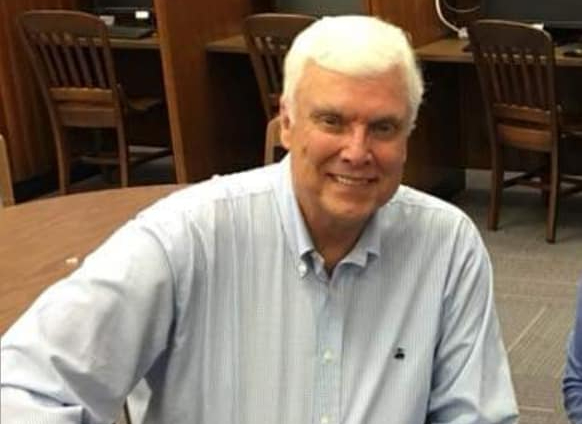

My former high school principal was a tall, distinguished, energetic man with a deep voice, snow-white hair, and a sharp eye. He was the very opposite of reticence. As our exchange over the phone that summer day reminded me, Mickey Dunn was a man who would tell the truth, warts and all. It was an honesty which added to his well-deserved reputation as a good coach and a dedicated educator.

In the summer of 2017, I was researching the history of the old Lawrenceburg City Cemetery, a lonely and solemn old burying ground tucked away on a tree-shrouded bluff in a quiet corner of our home of Lawrenceburg, Tennessee. I was planning a tour of the cemetery for that Halloween, and I wanted to locate every source that I could about the cemetery and the surrounding area.

Mickey’s family had once owned a sprawling farm across the street from the old cemetery. I had a sheaf of documents about the farm; deeds, tax cards, newspaper clippings, obituaries, census returns, old aerial photographs, and whatever else I had managed to dig up in the library’s local history room and the county Register’s office. But to get the heart and soul of the story, I knew there was only one man I could ask. And, like everyone in our community, I knew that he always answered the phone when someone needed help.

The story of how Mickey’s family came to settle on the old farm that now comprises a residential and business district on the western fringe of Lawrenceburg is a fascinating one. In the early days of Lawrenceburg’s history, a Methodist preacher named Noah Parker bought the place. He built a brick home on a knoll beside what was then the main road to Waynesboro, known locally as Waterloo Street. Rev. Parker’s home was incorporated into the Harris home in the 1990s, and is one of the only structures from that period in Lawrenceburg that survives today.

Noah’s daughter Mary Ann fell in love and married a fiery young attorney named Caleb Davis. Rev. Parker willed the half of the farm on the north side of Waterloo Street to the young couple, and they built a sprawling home on the property, just across the street from Rev. Parker’s old home. All was set for a grand happily-ever-after.

Until the Civil War began.

When Tennessee seceded from the Union, Davis made great speeches in support of secession. But when it became apparent that the war would not be over in a summer, and Federal troops first appeared on that western road beside Davis’s house in the spring of 1862, Davis experienced a sudden change of sympathies. When the Union army began administering the Oath of Allegiance to Confederate citizens, Davis later claimed that he was the first person in Lawrence County to travel to nearby Pulaski to take it.

After that, Davis threw his support entirely behind the Union cause, giving supplies to passing Union soldiers, even nursing a wounded Yankee through his final illness and burying him beside his own home (an interesting choice, given that he lived literally just yards away from the old city cemetery). Davis even spent three days hiding in nearby woods from Confederate guerillas who targeted him for execution due to his betrayal of the Cause.

So it will come as no surprise that, when a young Federal soldier came to town at war’s end in the spring of 1865 and wanted a place to stay while he established himself in business, he went to the one man in town whom he knew he could trust.

Thomas Dunn—Mickey’s aforementioned great-granddaddy—was a Kentucky-born soldier of Irish parentage. He volunteered for the Union army in 1861, and after his term of enlistment was done, he took on the role of sutler for the Union headquarters at nearby Pulaski. Thomas liked Tennessee, and he no doubt saw opportunity in the new economy that would rise from the ashes of the Confederacy.

And, despite his Yankee origins and Catholic faith, Thomas seems to have incorporated quickly into the social fabric of the community. By 1868, he was serving as a leader in a new social club alongside former Confederate officers. In a town that had been effectively abandoned during the war, in a county which would not recover its prewar population for two decades, Thomas’s sense of industry and desire to settle must have been a welcome relief to many of his former enemies.

Thomas lived for a while in an outbuilding behind the Davis home while he built a thriving and successful mercantile and timber business in Lawrenceburg. And, when Davis decided to leave Lawrenceburg for good in 1872, Thomas took the opportunity to buy his farm.

The Dunn family would own that land for generations, whittling parcels away bit-by-bit over the years through bequests and sales until finally the old farmhouse was demolished and the family cemetery exhumed and remains moved to the local Catholic cemetery in the mid-1960s.

As I pieced together this timeline, Mickey helped me fill in the gaps with recollections about family members who grew up there and personal anecdotes about the place. We called, texted, and met at the library half a dozen times that summer. He was not only willing to help me understand the history of his family farm, he was eager, often answering my questions at night.

But that was no surprise to me. That was the kind of man that Mickey Dunn was.

When my grandmother died my senior year in high school, Mr. Dunn found me in the cafeteria the next day before classes began. He extended a firm handshake to me, looked me in the eye, and said, “I’m sorry for your loss, Mr. Alley.” It was a moment of kindness that I will never forget. And that was just the tip of the iceberg of his kindness.

Mickey had a passion for helping people. He took special interest in the young people of our community who came from abusive or impoverished backgrounds, often taking them to doctor’s appointments when no one else could and showing them tough love and concern when no one else would. He believed in the power of mentorship, and changed the lives of many hard-pressed teenagers around a shared love for basketball. He also believed in the power of community, and saw the students under his care as an extended family. To Mickey, being a high school principal was not a job, it was a part of his identity.

Mickey was straightforward about his ancestor being a carpetbagger. But in recent years, a lot of southerners have come to realize that carpetbaggers, for the most part, were not bad folks. Far from the wicked and conniving hucksters of Gone With the Wind-fame, many of the people history remembers as “carpetbaggers” were humanitarians with an eye toward helping newly-freed slaves realize their potential. True, there were some opportunists in their number who sought to make a quick buck at the expense of economically-ravaged southerners, but those were probably more the exception than the rule.

Many carpetbaggers were former soldiers like Thomas, who came south with the army and liked it so much that they decided to return permanently and build a life here. Many more were teachers with a heart for the downtrodden, a mantle which Mickey Dunn would wear with pride a century-and-a-half later.

Mickey lost his battle with cancer on January 26, 2020. When he died, our community lost a mighty champion of learning, kindness, empathy, and honesty. But, as many of the speakers at his funeral attested, his legacy lives on in changed lives, in altered courses, and in restored dignity. Mickey Dunn planted seeds of kindness and love in places where few others dared go, and a mighty forest of integrity and self-worth will shade our community for generations to come as a result. He also left us a wonderful example to follow, and a crucial mission of empathy to continue.

Thanks, Mickey. For everything.