Who doesn’t love a tall tale? Over the next few weeks, I will examine some Lawrence County lore. After I present the facts, I will give each legend a rating of True, Mostly True, Mixture, Mostly False or False.

Local Legend: James K. Polk’s first official action as president of the United States was to fire the postmaster of Lawrenceburg, Tennessee.

My Rating: MOSTLY TRUE

James K. Polk, the eleventh President of the United States, was no stranger to Lawrence County. Although he lived in Columbia, Polk was admitted as a practicing attorney at the Lawrence County Court of Pleas and Quarter Sessions on October 2, 1820, and over the next two decades, his vocation and his political ambitions brought him frequently to court in Lawrenceburg.

The story goes that, when Polk was elected President of the United States in 1844, one of his first official acts as president was to fire Stephanus Busby, the postmaster of Lawrenceburg, because the two were somehow political enemies, or because Busby had somehow insulted Polk at one time.

The old legend, it is said, is particularly popular among Busby’s descendants.

As it turns out, the legend is probably true.

Polk took the oath of office as president of the United States on a stormy March 4, 1845. By April 19, just a month-and-a-half after Polk’s inauguration, Roberson D. Parish had replaced Stephanus Busby as the postmaster of Lawrenceburg, a job which Busby had held since 1839.

But there’s more.

On February 18, 1844, Polk was in Lawrenceburg for court. While he was there, he wrote a letter to two political allies in Nashville, instructing them to publish some particular speeches in the Nashville ‘Union’ as soon as possible. Nothing very unusual for a politician gearing up for a presidential race.

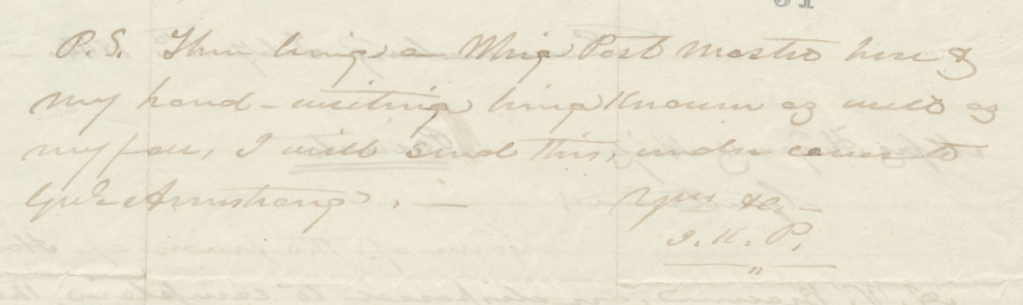

What was unusual about Polk’s letter on that day is that he added a postscript which said:

“P.S. There being a Whig Post master here & my hand-writing being known as well as my face, I will send this, under cover to Genl. Armstrong. J.K.P.”

This small note tucked away in Polk’s personal correspondence validates the fact that Polk was certainly distrustful of Busby, whose political leanings were apparently so passionate that Polk suspected him of losing or destroying mail to hurt Polk’s chances of election.

In fact, Polk was so suspicious of Busby that he had to get someone else to address the envelope, and he had to have it sent to a proxy recipient simply to ensure its delivery.

Having to go to such extraordinary lengths to get his mail through no doubt stuck with Polk, so we should not be surprised that a new postmaster was appointed for Lawrenceburg so quickly after Polk’s inauguration.

While I can’t confirm that firing Busby was the first thing Polk did after taking office, surviving evidence suggests that that Polk disliked and distrusted Busby, and that Busby was removed from office very soon after Polk became president. Therefore, I give this local legend a rating of MOSTLY TRUE.